Public-private partnership (PPP) agreements enable central and local government to attenuate more rapidly the "digital divide" in sparsely populated and unprofitable zones. They can take various forms according to the method of financing and the level of risk accepted by the private partner. Care must be taken to avoid unfair competition with the operators.

By definition, a PPP designates any form of partnership between a public authority and a private sector entity whose purpose is to finance, construct (or renovate), operate or maintain public infrastructures or to deliver a public service. This definition covers both technical assistance services and concessions.

A PPP offers several advantages for the public authority. First, it ensures good quality of service for citizens at optimal cost. It brings to public services and infrastructures the benefits of private sector methods, know-how and reactivity while avoiding pressure on public budgets, tax increases and borrowing.

PPP strengths and weaknesses

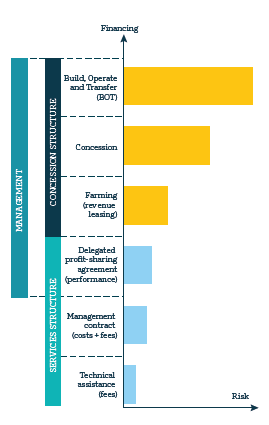

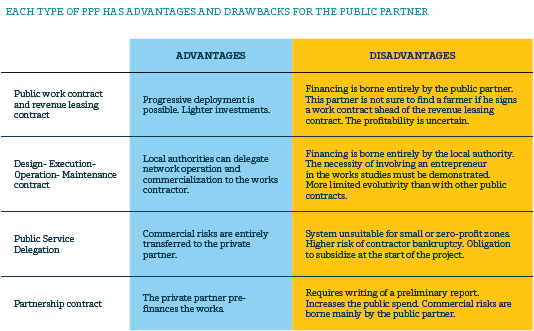

A variety of PPP structures are possible, depending on the private partner’s investment and tolerance of risks:

Optimized risk sharing

With PPP partnerships it is possible to transfer to each partner the risks that he is best able to control. To optimize the sharing of these risks, the partner’s abilities in four main areas must be assessed:

• Finance: finance the project at the best rates; borrow the project budget; manage the financing plan.

• Design and execution: study the requirements, specify the network, find the best contractors and supervise their work to be sure that the network meets the expressed needs.

• Operation: handle the network technical operation and assure the quality level imposed by the PPP.

• Sales: define and commercialize service offers, bill them and collect payments.

If the chosen model provides for sharing of the main risks, this must be stated.

When is a PPP appropriate to finance an FTTH network?

A PPP must not create unfair competition for operators, so the profitability of each deployment zone must be analyzed prior to signing the agreement. There are three possible situations:

FTTx zone with a break-even duration of no more than 10 years:

The PPP is not the right choice here.

• The zone is profitable, so it is reserved for operators.

• Infrastructure sharing should be encouraged under the

regulator’s control.

FTTx zone with a break-even duration of 10 to 15 (or even 20) years:

The PPP makes sense in these conditions.

• The government specifies the project (infrastructures, services, commercialization, etc.).

• Public financing is necessary.

• The private partner must assume the commercial risks.

Unprofitable zone:

The PPP is an option.

• The public partner is obliged to assume the commercial risks.

• Subsidies are predominant.

Zoom on the French model

The "France Très Haut Débit" program, intends to bring superfast Internet access to the entire population of France by the year 2022. The regulator ARCEP identifies two types of coverage zone:

• Very Dense Zones: about 150 French cities and large towns (Paris, Lyon, Marseille, etc.) in which all four private licensed operators Orange, SFR, Bouygues and Free will invest massively, rolling out their networks at the same time to take advantage of dense population and to counter competitors.

• Moderately Dense Zones: these are more disparate, ranging from dynamic town centers to extremely rural areas. In such zones a single operator deploys a network and then proposes a regulated wholesale offer to Internet service providers (ISP). For a so-called "governmentregulated" part of these zones, the government published an AMII (Appel à Manifestation d’Intention d’Investissement: Call for Expression of Interest to Invest). Two private operators, Orange and SFR-NC responded and are now committed with the State and the local authorities concerned to roll out FTTH in 3,600 municipalities. Outside this government-regulated zone, the territorial authorities themselves may deploy a "Public Initiative Network" (PIN).

The Public Initiative Network: an original solution

Owned by a regional or local authority, a PIN delivers services to homes and businesses through an ISP. In France the global spend will be €13-14 billion, part public, part private. Operating income and co-financing by ISPs cover half the total investment cost, the other half coming from public subsidies totaling €3.3 billion. To create their PINs, the authorities publish invitations to tender making use of various types of public contract: public works contract

followed by a "farming" contract, concessive public service delegation, public-private partnership (PPP), etc.

New players emerging

Many players bid for PIN projects: well-known telcos (Orange, SFR-NC), less visible operators (Axione, Altitude, Covage,...) and new entrants such as TDF. The Internet landscape finds itself deformed with a multitude of network operators on the fiber local loop and many small ISPs such as ozone, kiwi, k-net or Vitis challenging the big four national ISPs. Competition is intensifying both on networks and on end-users, which is a positive indicator that the race to fiber

deployment (some of it co-financed) is well underway.

The PIN as a lever for employment and territorial attractiveness

The PIN business model remedies lack of private initiative at a time when operators are extremely busy on several fronts: mobile license renewal, 5G mobile, VHSB rollout in very dense and government-regulated zones, co-financing, equipment, new digital usages...

The PIN is also a means of creating jobs in moderately dense zones. The "Observatoire 2017" survey of companies involved in PINs (http://observatoiredesrip.fr/) reports that in 2016. PINs created 8,100 full-time jobs, 35% more than in 2015. It also notes that entrepreneurial activity tends to be higher and unemployment lower in PIN areas than in zones without fiber.

VHSB technologies (FTTH, satellite, 4G Home) used in a PIN undeniably help to attenuate the digital divide and open up remote areas. They create value across the entire country, which explains the very rapid success of this very French model. Companies active on PINs appear confident: more than half of them expect to capitalize on their PIN experience by selling their savoir faire notably in Europe and Africa.

Public-private partnership (PPP) agreements enable central and local government to attenuate more rapidly the "digital divide" in sparsely populated and unprofitable zones. They can take various forms according to the method of financing and the level of risk accepted by the private partner. Care must be taken to avoid unfair competition with the operators.

By definition, a PPP designates any form of partnership between a public authority and a private sector entity whose purpose is to finance, construct (or renovate), operate or maintain public infrastructures or to deliver a public service. This definition covers both technical assistance services and concessions.

A PPP offers several advantages for the public authority. First, it ensures good quality of service for citizens at optimal cost. It brings to public services and infrastructures the benefits of private sector methods, know-how and reactivity while avoiding pressure on public budgets, tax increases and borrowing.

In France, Public Initiative Networks (PIN) require PPP agreements to finance FTTH (see page 15).

In Africa, a government entity in each country hosting a landing (cable termination) point of the ACE (African Coast to Europe) submarine communications cable - Equatorial Guinea, Mauritania, Gambia, Benin, Sao Tome and Principe, Gabon, and others - has negotiated a PPP contract with operators, in many cases an "operator of operators". In order to access international submarine cable capacity, a company has to be created to run the landing station.

The PPPs used are varied though similar in their general principles; each country defines operating rules compatible with its national laws. Partners have usage rights that depend on their investment, but they must pay for their reserved capacity (cable usage and station operation). Cable usage is "open" in

the sense that any licensed operator has the right to exploit the available capacity.

In Indonesia, a PPP has been made to construct and maintain sections of the national backbone that will serve the remaining unconnected parts of this very extensive archipelago of islands where communication routes are often poor. Remoteness and access difficulties considerably inflate connection expenses. The private partner is in charge of building and maintaining the backbone. The public partner, (the Universal Services Obligation fund), leases the network at a fixed price if the contractual monthly availability is attained and then sells the available capacity to operators.